Introducing Chaos Engineering Gadgets

Hey Inspektors! 👋

I am Bharadwaja Meherrushi Chittapragada, and I have been working under the mentorship of Michael Friese and Mauricio Vásquez Bernal as part of the LFX Mentorship Program. My project involved developing a set of gadgets for Inspektor Gadget to introduce system chaos (Issue #3196).

In this blog post, we'll dive into the chaos-inducing gadgets, exploring how they function, how they were built, and the alternatives we considered during development. We'll also talk about the changes made along the way and why we made those decisions. But before we jump in, let's take a quick look at Inspektor Gadget and how chaos engineering fits into the picture.

What is Inspektor Gadget?

Inspektor Gadget is a framework and toolset for data collection and system inspection on Kubernetes clusters and Linux hosts using eBPF. It simplifies the packaging, deployment, and execution of Gadgets (eBPF programs encapsulated in OCI images) and provides customizable mechanisms to extend their functionality.

Read more in the official docs.

What is Chaos Engineering, and what gadgets could help?

Chaos Engineering is all about testing a system's ability to handle unexpected disruptions and stressful conditions in production (ref: Principles of Chaos). In simple terms, it means intentionally introducing faults or disruptions to see how the system responds. The idea is to create gadgets that can inject chaos into the system, so developers can test the system's resilience in a controlled environment and build fallback mechanisms for potential production disruptions.

The goal of this project was to build gadgets that introduce chaos into systems.

With eBPF, we could trigger these disruptions in a few ways:

- Changing the return values of kernel functions

- Dropping or modifying network packets

- Simulating system call failures

The main objective was to develop a set of gadgets in Inspektor Gadget that make it easy to test system chaos. Here are some ideas for the gadgets we have implemented:

- DNS: Drop DNS requests and/or responses based on:

- The container or process that initiated the request

- The target URL

- The DNS server

- TCP/UDP: Drop network packets based on:

- Source or destination IP addresses

- The originating or destination pod or process

- Syscalls: Simulate system call failures based on:

- The container or process performing the syscall

- Specific system calls

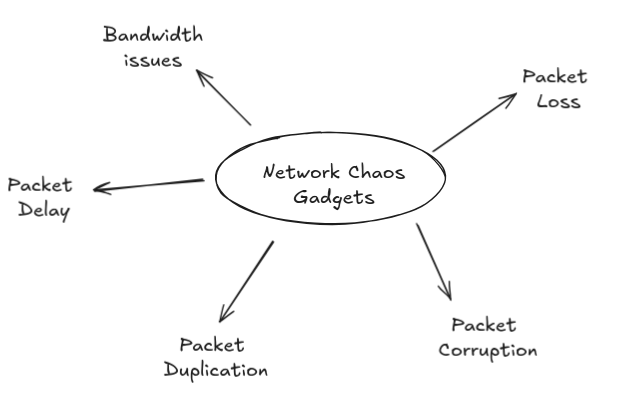

Network Chaos Gadgets

Network failures are a frequent occurrence and should be rigorously tested before deploying applications on a Kubernetes cluster. The network primarily encounters three types of issues:

- Random Packet Drops: Unexpected loss of packets during transmission.

- Random Bit Flips: Corruption of data due to flipped bits in the packets.

- Packet Delays: Latency introduced due to delays in packet delivery.

- Packet Duplication: Introducing duplicate packets into the network stream.

- Bandwidth Issues: Simulating reduced or fluctuating network bandwidth.

For now, we decided to focus on building gadgets to address the first three issues.

We introduced these disruptions using eBPF programs attached to TC (Traffic Control) hook points. Some programs could also be attached to the XDP hookpoint, which is available only at ingress. XDP handles packets at the earliest possible point---directly in the driver---before sk_buff allocation. However, Inspektor Gadget doesn't support the XDP hookpoint just yet, but we plan to add support for it after building the initial set of gadgets.

Random Drop packet

Understanding Packet Loss in Real-World Networks

In the intricate ecosystem of network communications, packet loss is not an anomaly but a natural phenomenon. Networks are complex, dynamic systems where data transmission is subject to numerous environmental and infrastructural challenges. In real-world network scenarios, packets can be dropped due to various reasons:

| Cause of Packet Loss | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Network Congestion | Overloaded network routes | Reduced throughput |

| Hardware Limitations | Network device capacity | Intermittent connectivity |

| Transmission Errors | Signal degradation | Data integrity issues |

| Routing Problems | Inefficient path selection | Communication breakdowns |

| Bandwidth Constraints | Insufficient network capacity | Performance degradation |

These seemingly random disruptions are not just technical nuisances but critical factors that can significantly impact application performance, user experience, and system reliability. By understanding and simulating these network imperfections, we can build more robust, resilient software systems that gracefully handle unexpected network conditions.

Probabilistic Packet Loss Modeling

Bernoulli Probability

When we seek to simulate network packet loss, we turn to probability theory -- specifically, the Bernoulli distribution. The Bernoulli model provides a simple yet powerful mechanism to model independent, random events with a fixed probability of occurrence. In our network context, each packet has an independent, predefined chance of being dropped, mirroring the unpredictable nature of real-world network communications.

// Probabilistic packet drop mechanism using Bernoulli distribution

static int rand_pkt_drop_map_update(struct event *event,

struct events_map_key *key,

struct sockets_key *sockets_key_for_md)

{

// Generate a cryptographically secure random number

__u32 rand_num = bpf_get_prandom_u32();

// Calculate drop threshold based on configured loss percentage

volatile __u64 threshold =

(volatile __u64)((volatile __u64)loss_percentage *

(__u64)0xFFFFFFFF) / 100;

// Probabilistic packet drop

if (rand_num <= (u32)threshold)

{

// Detailed event logging

event->drop_cnt = 1;

return TC_ACT_SHOT; // Drop the packet

}

return TC_ACT_OK; // Allow packet to pass

}

Alternative Approaches (NetEm and Markov chain models)

Network Emulation (NetEm) is a powerful tool in the Linux kernel that allows for the simulation of various network conditions, such as latency, packet loss, duplication, and reordering. NetEm operates at the network layer and can be configured using the tc (traffic control) command. It provides a flexible and comprehensive way to introduce network impairments for testing purposes.

Using NetEm for Packet Loss

NetEm can simulate packet loss using a variety of models, including Bernoulli and Gilbert-Elliott models. The Bernoulli model introduces random packet loss based on a fixed probability, similar to our eBPF implementation. The Gilbert-Elliott model, on the other hand, uses a two-state Markov chain to simulate bursty packet loss, which is more representative of real-world network conditions.

For now, we have chosen to proceed with the Bernoulli model due to its simplicity and suitability for the space and complexity constraints inherent in eBPF programs. Additionally, we are planning to include the Gilbert-Elliott model in the future to better simulate bursty packet loss scenarios, providing a more comprehensive testing environment.

# Example: Simulate 10% packet loss using NetEm

tc qdisc add dev eth0 root netem loss 10%

Why We Chose eBPF Over NetEm

While NetEm is a powerful tool, our goal was to leverage eBPF to achieve similar functionality. eBPF offers several advantages:

- Performance: eBPF programs run in the kernel, providing high performance with minimal overhead.

- Granularity: eBPF allows for fine-grained control over individual packets, enabling more precise manipulation.

- Integration: eBPF can be integrated directly into existing frameworks like Inspektor Gadget, providing a seamless experience for users.

By using eBPF, we aim to create a flexible and efficient solution for simulating network impairments, tailored to the specific needs of our project.

Configurable Gadget Parameters

The implementation offers granular control over packet dropping through a set of configurable parameters:

const volatile struct gadget_l3endpoint_t filter_ip = { 0 };

const volatile __u16 port = 0;

const volatile __u32 loss_percentage = 100;

const volatile bool filter_tcp = true;

const volatile bool filter_udp = true;

const volatile bool ingress = false;

const volatile bool egress = true;

These parameters enable precise targeting of packet drops:

- Specific IP addresses (IPv4 and IPv6)

- Particular network ports

- Protocol-specific filtering (TCP/UDP)

- Network direction (ingress/egress)

- Configurable loss percentage

The protocol selection parameters, filter_tcp and filter_udp, allow control over the type of packets to drop, enabling or disabling packet drops for TCP and UDP protocols, respectively. Additionally, the network direction hooks, ingress and egress, determine whether the filtering applies to incoming or outgoing packets, providing flexibility in simulating network conditions for specific traffic directions.

Filtering Scenarios

| IP Filter | Port Filter | Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Unspecified | Unspecified | Drop all packets* |

| Specified | Unspecified | Drop packets for specific IP* |

| Unspecified | Specified | Drop packets for specific port* |

| Specified | Specified | Drop packets matching both IP and port* |

*Always drop packets based on loss percentage and default loss percentage is 100%

Optimization

The implementation emphasizes computational efficiency through early-stage packet filtering:

static __always_inline int packet_drop(struct __sk_buff *skb)

{

// Early protocol and header validation

if ((void *)(eth + 1) > data_end) {

```c

return TC_ACT_OK; // Eth headers incomplete - Letting them pass through without further processing

}

// Protocol-specific processing

switch (bpf_ntohs(eth->h_proto)) {

default:

return TC_ACT_OK; // Unhandled protocol, pass through

case ETH_P_IP: // IPv4 Processing

if (filter_ip.version == 6)

return TC_ACT_OK; // If filtering IPv6, let IPv4 pass through

ip4h = (struct iphdr *)(eth + 1);

// Check if IPv4 headers are invalid

if ((void *)(ip4h + 1) > data_end)

return TC_ACT_OK;

// Early filtering based on IP address

if (ingress && filter_ip.addr_raw.v4 != 0 &&

(filter_ip.addr_raw.v4 != ip4h->saddr))

return TC_ACT_OK;

if (egress && filter_ip.addr_raw.v4 != 0 &&

(filter_ip.addr_raw.v4 != ip4h->daddr))

return TC_ACT_OK;

event.src.addr_raw.v4 = ip4h->saddr;

key.dst.addr_raw.v4 = ip4h->daddr;

event.src.version = key.dst.version = 4;

sockets_key_for_md.family = SE_AF_INET;

switch (ip4h->protocol) {

case IPPROTO_TCP:

if (!filter_tcp)

return TC_ACT_OK;

struct tcphdr *tcph =

(struct tcphdr *)((__u8 *)ip4h +

(ip4h->ihl * 4));

if ((void *)(tcph + 1) > data_end)

return TC_ACT_OK;

// Early filtering based on port

if (ingress && port != 0 &&

port != bpf_ntohs(tcph->source))

return TC_ACT_OK;

if (egress && port != 0 &&

port != bpf_ntohs(tcph->dest))

return TC_ACT_OK;

event.src.proto_raw = key.dst.proto_raw = IPPROTO_TCP;

event.src.port = bpf_ntohs(tcph->source);

key.dst.port = skb->pkt_type == SE_PACKET_HOST ?

bpf_ntohs(tcph->dest) :

bpf_ntohs(tcph->source);

sockets_key_for_md.proto = IPPROTO_TCP;

break;

}

}

}

The TC_ACT_OK action is used to filter out packets that do not meet our criteria, allowing them to pass through without further processing. This ensures that we only collect data on packets that are relevant to our specific filtering conditions, optimizing performance and focusing our analysis on the targeted traffic. By performing early filtering, we reduce the computational overhead and improve the efficiency of the packet processing pipeline.

This approach ensures minimal computational overhead by quickly passing through packets that don't match filtering criteria.

Logging and Observability

Comprehensive event capture is crucial in chaos engineering:

struct event {

gadget_timestamp timestamp_raw;

struct gadget_l4endpoint_t src;

gadget_counter__u32 drop_cnt;

bool ingress;

bool egress;

gadget_netns_id netns_id;

struct gadget_process proc;

};

The event structure captures rich metadata about dropped packets, enabling detailed analysis and understanding of network behavior under simulated stress conditions.

In Inspektor Gadget, there are two main metric strategies:

-

User-Space Event Reporting: Metrics are generated by sending events from eBPF programs to user-space. This method is easy to implement and suitable for lower throughput scenarios. It uses annotations in

gadget.yamlor macros in eBPF struct definitions to define metrics. -

eBPF Map-Based Metrics: Metrics are stored directly in eBPF maps, making this method more efficient for high-throughput scenarios like packet processing. It minimizes overhead and allows for fast performance, especially when exporting data to systems like Prometheus.

For the packet-dropping gadget, we chose eBPF map-based metrics due to its ability to efficiently handle high-throughput data with minimal overhead, ensuring fast performance while processing and tracking large volumes of packets.

Check the output format of the gadget on https://inspektor-gadget.io/docs/latest/gadgets/chaos_packet_drop

Bit flip gadget

- Follows very similar story to that of the random drop gadget but just a change in the function

rand_pkt_drop_map_updatetorand_bit_flip_map_update.

So, instead of dropping packets randomly, we call a random_bit_flip function on random packets.

static __always_inline int rand_bit_flip(struct __sk_buff *skb, __u32 *data_len)

{

// Ensure the packet has valid length

if (*data_len < 1) {

return TC_ACT_OK;

}

// Get a random offset and flip a bit

__u32 random_offset = bpf_get_prandom_u32() % *data_len;

__u8 byte;

// Use bpf_skb_load_bytes() to load the byte at the random offset

if (bpf_skb_load_bytes(skb, random_offset, &byte, sizeof(byte)) < 0) {

return TC_ACT_OK; // Error in loading byte, return OK

}

// Flip a random bit in the byte

__u8 random_bit = 1 << (bpf_get_prandom_u32() % 8);

byte ^= random_bit;

// Use bpf_skb_store_bytes() to store the modified byte back to the packet

if (bpf_skb_store_bytes(skb, random_offset, &byte, sizeof(byte), 0) < 0) {

return TC_ACT_OK; // Error in storing byte, return OK

}

return TC_ACT_OK;

}

The rand_bit_flip function is designed to introduce randomness into network traffic by flipping a single bit in a packet's payload. First, it checks if the packet has a valid length; if the length is less than 1 byte, the function does nothing and returns TC_ACT_OK, allowing the packet to pass through unchanged. Then, a random offset within the packet is chosen based on the packet's data length. Using this offset, the function loads the byte at that position with the bpf_skb_load_bytes() helper. If this operation is successful, it randomly selects a bit within the byte and flips it by applying an XOR operation (^=) with a randomly chosen bit. After the modification, the byte is written back into the packet using bpf_skb_store_bytes().

If any of these operations fail, the function ensures the packet continues to flow through the network stack without disruption by returning TC_ACT_OK. The function allows for random bit flipping, simulating errors or disturbances in network traffic.

- The current logic does not encorporate

checksumrecalculation but we plan on integrating that soon.

Introducing Support for IPv4 and IPv6 as Gadget Parameters

Initially, there was no support for accepting IP parameters directly as inputs for the gadget, we introduced support for both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses as parameters.

Parsing and Storing IP Addresses

The first step in the process was updating the Start function in the pkg/operators/ebpf/ebpf.go file. This function is responsible for processing the parameters passed to the eBPF program. We needed to ensure that when the program encounters an IP address, it can differentiate between IPv4 and IPv6. Using Go's net.IP type, we wrote logic to check whether the IP address is IPv4 or IPv6 and store it accordingly.

if ip := ipParam.To4(); ip != nil {

ipAddr.Version = 4

copy(ipAddr.V6[:4], ip) // Store the first 4 bytes for IPv4 in the V6 field

} else if ip := ipParam.To16(); ip != nil {

copy(ipAddr.V6[:], ip) // Store the full 16 bytes for IPv6

ipAddr.Version = 6

} else {

return fmt.Errorf("invalid IP address: %v", ipParam)

}

The L3Endpoint Struct

To store both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses in a consistent format, we created a new struct called L3Endpoint in the pkg/operators/ebpf/types/types.go file. The struct holds a 16-byte array (V6) for the IP address and an 8-bit Version field to indicate whether the address is IPv4 or IPv6:

type L3Endpoint struct {

V6 [16]byte // IPv6 address (also used for IPv4)

Version uint8 // 4 for IPv4, 6 for IPv6

_ [3]byte // Padding for alignment

}

Type Hinting for IP Parameters

To ensure that the eBPF program recognizes when a parameter is an IP address, we updated the type hinting system. Specifically, we modified the getTypeHint function in the pkg/operators/ebpf/params.go file to return params.TypeIP for the L3Endpoint type. This tells the program that the parameter should be treated as an IP address.

switch typedMember.Name {

case ebpftypes.L3EndpointTypeName:

return params.TypeIP

}

This change ensures that when the eBPF program encounters a parameter of type L3Endpoint, it knows the data is an IP address and processes it accordingly.

Setting Default Values for IP Addresses

Finally, we needed to ensure that there are sensible default values for IP addresses in case no specific address is provided. In the pkg/operators/ebpf/params_defaults.go file, we set the default value for IPv4 to 0.0.0.0. This ensures that the system has a valid IP address (even if it's just the default) when no address is specified.

case *btf.Struct:

switch t.Name {

case ebpftypes.L3EndpointTypeName:

defaultValue = "0.0.0.0" // Default value for IPv4

}

This ensures that if no IP address is provided, the system defaults to 0.0.0.0 for IPv4 addresses, ensuring the program can continue running without errors.

DNS Delay Gadget

In the world of network performance testing and chaos engineering, introducing artificial delays can be an invaluable tool. One of the ways this can be done is by delaying specific network packets, such as DNS (Domain Name System) packets, to test how systems behave under network latency.

The challenge here was to develop an eBPF-based gadget that could delay DNS packets (UDP packets on port 53) without affecting other types of network traffic. The gadget needed to:

- Identify DNS packets in both IPv4 and IPv6 formats.

- Introduce a delay in the timestamp of these packets before they left the system.

- Maintain efficiency and minimize overhead.

Exploring Packet Delay in eBPF: Challenges and Solutions

When working with eBPF, implementing a delay for network packets proved to be challenging due to several constraints, particularly with functions like tc or xdp programs, which could not sleep. The typical approach of introducing a sleep or delay in the code wasn't feasible in these contexts due to eBPF's limitations. However, we explored alternative solutions that made use of other kernel features, such as timers and queuing mechanisms.

Issue 1: eBPF Programs Couldn't Sleep

The first issue we encountered when trying to delay packets using eBPF was the fact that eBPF programs, like XDP (eXpress Data Path), were not designed to be sleepable. This meant we couldn't directly use traditional methods like sleep() to introduce delays. One potential solution we explored was the use of bpf_timers, which allowed us to manage timeouts or delays within kernel space, although it required careful handling.

Issue 2: Storing Packets Temporarily

Although bpf_timers offered a potential solution, another challenge arose when we attempted to store packets temporarily for later reinjection after a delay. To achieve this, we needed to store the packets in a map, which required the ability to uniquely identify each packet. We also had to consider the feasibility of how many packets could be stored in the map at once, and whether packets beyond the map's capacity should be dropped.

One limitation in this approach was that we couldn't store the skb (socket buffer) structure directly in the map. As a solution, we decided to copy the packet into the map and then drop the original packet, ensuring it could be reinjected later after the delay. Given that DNS packets, the target for this approach, have a maximum size of 512 bytes, this architecture became viable for small packets like these.

Attempting a Busy Wait with eBPF

An important part of the delay mechanism was the ability to pause or introduce a "busy wait." However, eBPF's verifier imposed strict limitations on loops and certain control flow constructs, preventing us from implementing traditional busy-wait mechanisms. We tried various methods such as mathematical calculations, switch statements, and goto constructs, but the verifier rejected these due to the complexity of the timing behavior they introduced.

Community Insights and the FQ qdisc Solution

After exploring these options and hitting roadblocks, we reached out to the eBPF community for guidance. One helpful response pointed to the current limitations in eBPF, explaining that kernel developers had not yet added features to support packet delays solely within eBPF programs. Instead, the recommended approach involved using eBPF to interact with existing logic, specifically the FQ (Fair Queueing) qdisc, which could be used to manage packet delays.

As explained, while eBPF itself didn't support delaying packets directly, we could instruct the kernel to delay packets using the FQ qdisc by setting the delay time in the eBPF program. Cilium, a popular networking project, leveraged this approach by configuring the delay time in eBPF and relying on the kernel's FQ qdisc to handle the actual packet queuing and delay.

Limitations of the FQ qdisc Approach

The FQ qdisc method did come with a couple of important limitations.

-

First, it only worked on egress traffic, meaning it couldn't be used for ingress packet delays.

-

Second, the maximum delay that could be introduced was 1 second by default. This was due to the "drop horizon" feature in the FQ qdisc, which ensured that packets delayed beyond a certain threshold were dropped to prevent excessive queuing. The default value for this drop horizon was 1 second, but there was ongoing exploration into whether this value could be adjusted.

Despite these limitations, the FQ qdisc approach remained viable for many use cases, especially when a small delay was sufficient, such as in DNS traffic, where delays on the order of 1 second were often acceptable.

The Final Approach:

After considering several approaches, we decided to implement a traffic classifier eBPF program attached to the egress hook at the FQ qdisc. This program would:

-

Inspect Network Packets: It would inspect the Ethernet, IP, and UDP headers to identify DNS packets based on the port number (53).

-

Introduce a Delay: Upon identifying DNS packets, we captured the current time, added a predefined delay (500 ms), and then modified the packet's timestamp (

skb->tstamp) to simulate network latency using the FQ (Fair Queueing) qdisc. The FQ qdisc handled the actual queuing and delay of packets, ensuring efficient and controlled packet delay. -

Track and Log Events: Additionally, we implemented an optional system to track events using an eBPF map to store metadata about the delayed packets, such as the source and destination IPs, process information, and timestamps. This was kept optional, as the information collection would introduce overhead.

The key decision was to use eBPF because it allowed for direct manipulation of packets in the kernel, leading to high performance with minimal overhead.

Explanation of the Code:

Now, let's take a closer look at the core parts of the implementation, specifically the eBPF program that handles packet classification and delay introduction.

delay_ns:

At the start of the code, we defined some essential constants and included the necessary headers. The constant delay_ns was set to 500 milliseconds (500,000,000 nanoseconds) and was used to simulate the delay.

const volatile __u64 delay_ns = 500000000; // 500ms in nanoseconds

Main Packet Processing Logic:

The main logic was contained in the function delay_dns_packets, which was attached to the egress traffic classifier (SEC("classifier/egress/drop")). It processed the packet, checked if it was a DNS packet, and if so, introduced the delay.

-

Packet Parsing: First, we parsed the Ethernet, IPv4, and IPv6 headers to ensure the packet was valid and to identify the protocol.

struct ethhdr *eth = data;

struct iphdr *ip4h;

struct ipv6hdr *ip6h;

if ((void *)(eth + 1) > data_end) {

return TC_ACT_OK; // Eth headers incomplete - Let them pass through

}

switch (bpf_ntohs(eth->h_proto)) {

case ETH_P_IP: // IPv4 Processing -

Handling IPv4 DNS Packets: If the packet was IPv4 and the protocol was UDP, we checked the source and destination ports. If the port was 53 (DNS), we modified the timestamp to simulate the delay.

if(ip4h->protocol == IPPROTO_UDP) {

struct udphdr *udph = (struct udphdr *)((__u8 *)ip4h + (ip4h->ihl * 4));

if (bpf_ntohs(udph->dest) == 53 || bpf_ntohs(udph->source) == 53) {

__u64 current_time = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

skb->tstamp = current_time + delay_ns; // Add delay to timestamp

...

}

} -

Handling IPv6 DNS Packets: Similarly, for IPv6 packets, we checked if the packet was UDP with port 53 and introduced the delay.

case ETH_P_IPV6: // IPv6 Processing

ip6h = (struct ipv6hdr *)(eth + 1);

if(ip6h->nexthdr == IPPROTO_UDP) {

struct udphdr *udph = (struct udphdr *)(ip6h + 1);

if (bpf_ntohs(udph->dest) == 53 || bpf_ntohs(udph->source) == 53) {

__u64 current_time = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

skb->tstamp = current_time + delay_ns; // Add delay to timestamp

...

}

}

break; -

Logging the Event: Once a DNS packet was identified and delayed, we stored the event in the

events_mapusing the destination address and port as the key. We also enriched the event with process information, network namespace ID, and the delay.bpf_map_update_elem(&events_map, &key, &event, BPF_NOEXIST);

We still need to improve the gadget to take the URL as the gadget parameter.

This delay gadget was useful for simulating DNS latency in network testing, chaos engineering, and performance benchmarking.

Improvements that we are still undergoing/planned:

- Checksum correction in the bit_flip gadget

- URL parameter for the DNS gadget

- Dynamic configuration of the parameters by maintaining a map

System Chaos failures

The initial concept was to simulate system call failures based on specific criteria:

- Container or Process: This could be achieved by using the

mount_idas a gadget parameter. - Syscall: We focused on intercepting specific syscalls by attaching eBPF programs at the respective kprobes.

Once intercepted, we could use functions like bpf_override_return() or bpf_send_signal() to either return an error code when a system call is made or kill the process executing the syscall. Additionally, we could gather statistics using the gadget's buffer.

However, we now plan to integrate this system chaos feature with ongoing work on event generation. The goal is to provide more than just observability, as there can be significant overhead when combining chaos engineering with event generation. This integration faces several challenges:

- Limitations of eBPF: Not all functionality can be implemented directly within eBPF.

- Runtime Configurability: Some actions may need to be configurable during runtime.

- Injection and Manipulation: The system needs to support both injection and manipulation, which requires creating a new class of gadgets to handle these actions efficiently.

This integration will enable us to create more dynamic and configurable chaos engineering tools while maintaining the flexibility needed for event generation.

Mentorship Experience

I am incredibly grateful to my mentors, Michael Friese and Mauricio Vásquez Bernal, for their exceptional guidance and support throughout the LFX Mentorship Program. They were patient, understanding, and always willing to address my questions—no matter how small—despite their busy schedules. Their flexibility and encouragement made it easier to navigate the project alongside my academic commitments. I deeply appreciated how they pushed me to improve my communication skills and actively engage with the community, fostering both my technical and interpersonal growth. Their unwavering support and constructive feedback were instrumental in making this mentorship an enriching and enjoyable experience. I have nothing but the utmost gratitude for their time, effort, and belief in my potential. Thank you for being amazing mentors!

Conclusion

In this blog, we reviewed the chaos gadgets implemented and the thought process behind their development. If there is scope for improvement of logic or requirement of more customization, feel free to reach us out.

For more details, check out the Inspektor Gadget’s repository. If you encounter any issues while creating your test files don’t hesitate to reach out on Slack. We’re always happy to help!

Happy Inspekting!