Implementing Unit Tests

Hello Inspektors,

I am Shaheer, a CS Major at LUMS, Pakistan, and I have been working under the mentorship of Burak Ok and Qasim Sarfraz for the past 3 months as part of LFX mentorship. My project was to implement unit tests for Inspektor Gadget by:

a) Refactoring the existing code to be more unit-test friendly

b) Designing and implementing unit tests from scratch

For the last part of the mentorship, I also worked on a new gadget, Snapshot File.

In this blog, I will be taking you through the challenges and questions that I faced, and how I resolved them.

Why are unit tests important

Let’s first think about why tests in general are important for big systems. For systems that are continuously growing (like Inspektor Gadget), we need a sanity check to ensure that a newly introduced change hasn’t broken anything. This is where tests come in. They hold your system together like glue—the more tests you have, the less the chances of your code breaking unexpectedly in the event of a change.

The reason why unit tests in particular are important for a logically intense system is that they provide highly focused coverage and highly granular information about where things went south. Additionally, unit tests are fast to execute, which helps reduce development time and provides quicker feedback when something isn’t working or behaving as expected.

While these tests are brittle to change, it is generally a good idea to have extensive unit tests for established, logically complex codebases.

How I started

Initially, I was surprised to see that the existing unit tests in the codebase were not theoretically very “unit”—e.g., for operators, the entire lifecycle of a gadget was being mimicked to test some post-processing (operator) code.

My first attempt was to test this code in a more “unit” way. I was able to do so by instantiating raw data sources and directly calling the functions that were doing the main work, instead of triggering the gadget lifecycle.

These “functions” were not properly defined in many cases, in which case I had to first refactor the existing operator code to migrate the main logic into a separate function and then test that directly.

A minimal and easy-to-understand example would be the following snippet in CLI operator, responsible for displaying data when the outpute mode of the datasource is yaml. To test this, I would have had to go through the extensive boilerplate code in the PreStart() function, which could not have been tested without instantiating the operator itself.

ds.Subscribe(func(ds datasource.DataSource, data datasource.Data) error {

yml, err := yaml.JSONToYAML(jsonFormatter.Marshal(data))

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("serializing yaml: %w", err)

}

fmt.Println("---")

fmt.Print(string(yml))

return nil

}, Priority)

Instead, I abstracted away the main portion of the code into a new function, while inverting the dependency on the real data source, real data, and direct stdout printing by introducing parameters for them. In the test cases, I was able to pass the locally instantiated data sources and data, as well as a bytes.Buffer instead of os.Stdout, to capture the output. This way, I was able to test the code without having to mimick the entire gadget lifecycle.

ds.Subscribe(func(ds datasource.DataSource, data datasource.Data) error {

return yamlDataFn(ds, data, jsonFormatter, os.Stdout)

}, Priority)

//...

func yamlDataFn(

ds datasource.DataSource,

data datasource.Data,

jsonFormatter *json.Formatter,

w io.Writer,

) error {

yml, err := yaml.JSONToYAML(jsonFormatter.Marshal(data))

if err != nil {

return fmt.Errorf("serializing yaml: %w", err)

}

fmt.Fprintln(w, "---")

fmt.Fprint(w, string(yml))

return nil

}

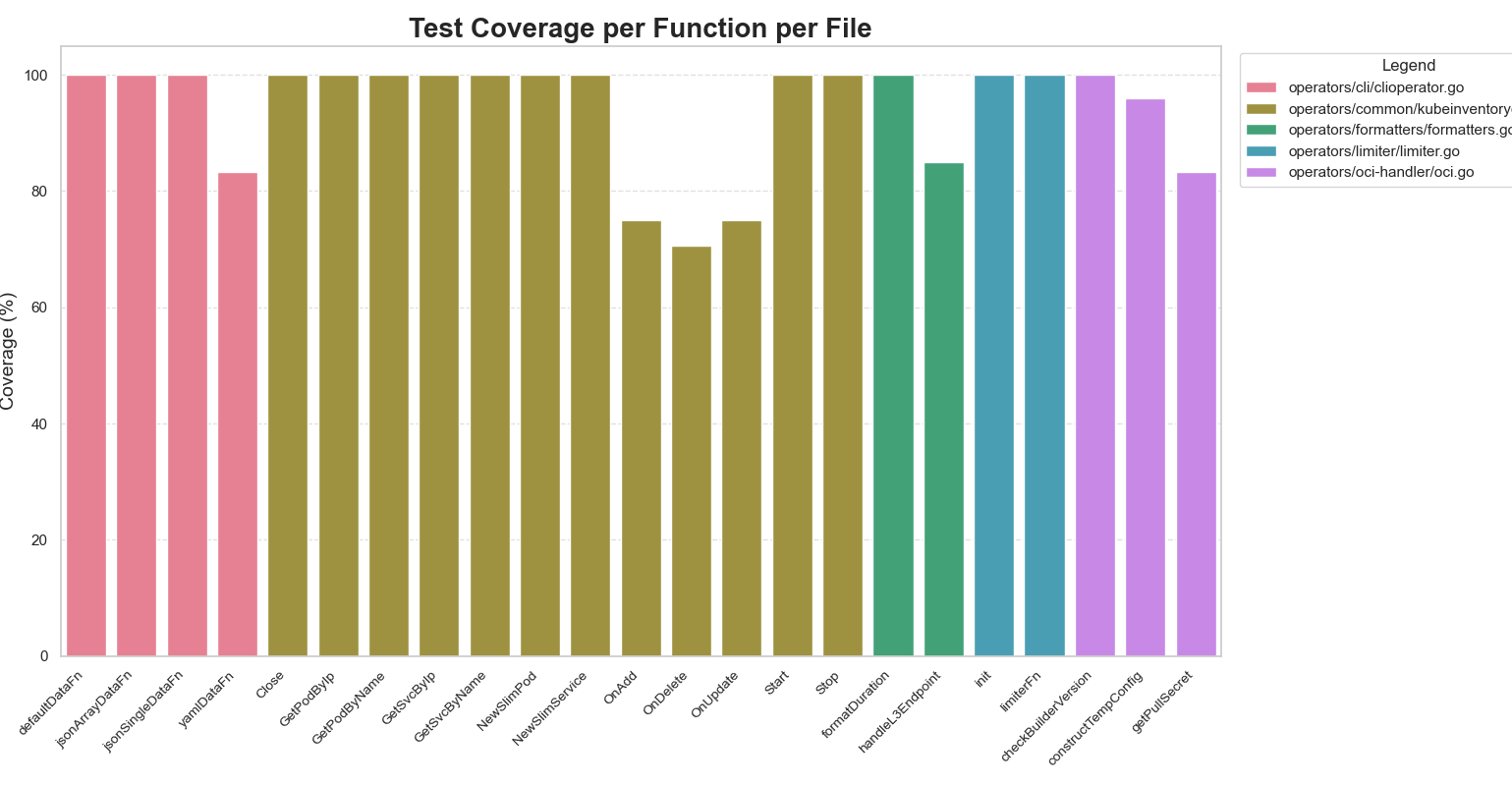

Following the same philosophy, for the first half of the mentorship, I designed and implemented extensive unit tests for these operators:

The following graph shows the increment in the coverage that I achieved for each of the main functions in the operators. While most files show high test coverage, the few that fall below 100% contain gadget lifecycle-specific code paths that are difficult to cover with unit tests and are better suited for integration testing.

The results can be verified by analyzing the coverage profile emitted by the command:

go test -coverprofile=coverage.out ./your/package/path

Unit tests for gadgets

The existing unit tests for the trace_open gadget (the only gadget that had unit tests implemented already) were generating the open syscall explicitly and testing the gadget in a more end-to-end manner. I had the same questions here: why are we triggering the entire gadget if we just have to test some BPF logic written in C?

The culprit was the fact that “the how is not separated from the why” in BPF programs. While there exists a framework, BPF_PROG_RUN, to unit test BPF programs, for kprobe-based BPF programs, there was no such framework. Therefore, I was left with no choice but to test the gadgets in a more end-to-end manner, i.e., by triggering syscalls and recording events manually.

Thanks to Sanskar Sharma's LFX project, there already exists a gadgetRunner framework that does the heavy lifting for you, which I used to write comprehensive unit tests for:

New Gadget: Snapshot File

After writing a lot of unit tests, I wanted to do something new for the codebase.

On the suggestion of my mentors, I decided to implement a new gadget—Snapshot File—which lists all the files open by all the tasks with different types.

I went through this very helpful guide to understand how to write the BPF code for a gadget, and using the task_file BPF iterator, I was able to implement the gadget. This iterator basically invokes the BPF code for every (task, file) pair.

The gadget is currently in review and hopefully will be merged in the near future.

All of my work can be seen at this link.

Conclusion

Working on Inspektor Gadget over the past three months has been an incredibly rewarding experience. Not only did I get to dive deep into unit testing and learn about writing more modular, testable code, but I also gained hands-on exposure to BPF programming and system-level tooling.

A huge shoutout to my fantastic mentors, who were always there to answer all of my questions—however dumb they were. You played an integral role in making this mentorship an amazing experience for me.

Thanks for reading!